An increasing number of scientists have come to the conclusion that the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate is the key factor in understanding how lithium works. Lithium has been shown to change the inward and outward currents of glutamate receptors (especially GluR3), without a. Li I Ground State 1s 2 2s 2 S 1 / 2 Ionization energy 43487.150 cm-1 (5.391719 eV) Ref. K87 Li II Ground State 1s 2 1 S 0 Ionization energy 610078 cm-1 (75.6400 eV) Ref. Lithium was a chemical element, number 3 on the periodic table.It was the lightest alkali metal on the table, with an atomic weight of 6.91. (TNG: 'Rascals') Lithium in a crystal form was utilized in 'lithium crystal circuits,' important components in the power-generation systems of Constitution-class starships. The hydrogen of hydrogen bombs is actually the compound lithium hydride, in which the lithium is the lithium-6 isotope and the hydrogen is the hydrogen-2 isotope (deuterium). This compound is capable of releasing massive amounts of energy from the neutrons released by the atomic bomb at its core.

The Element Lithium

[Click for Isotope Data]

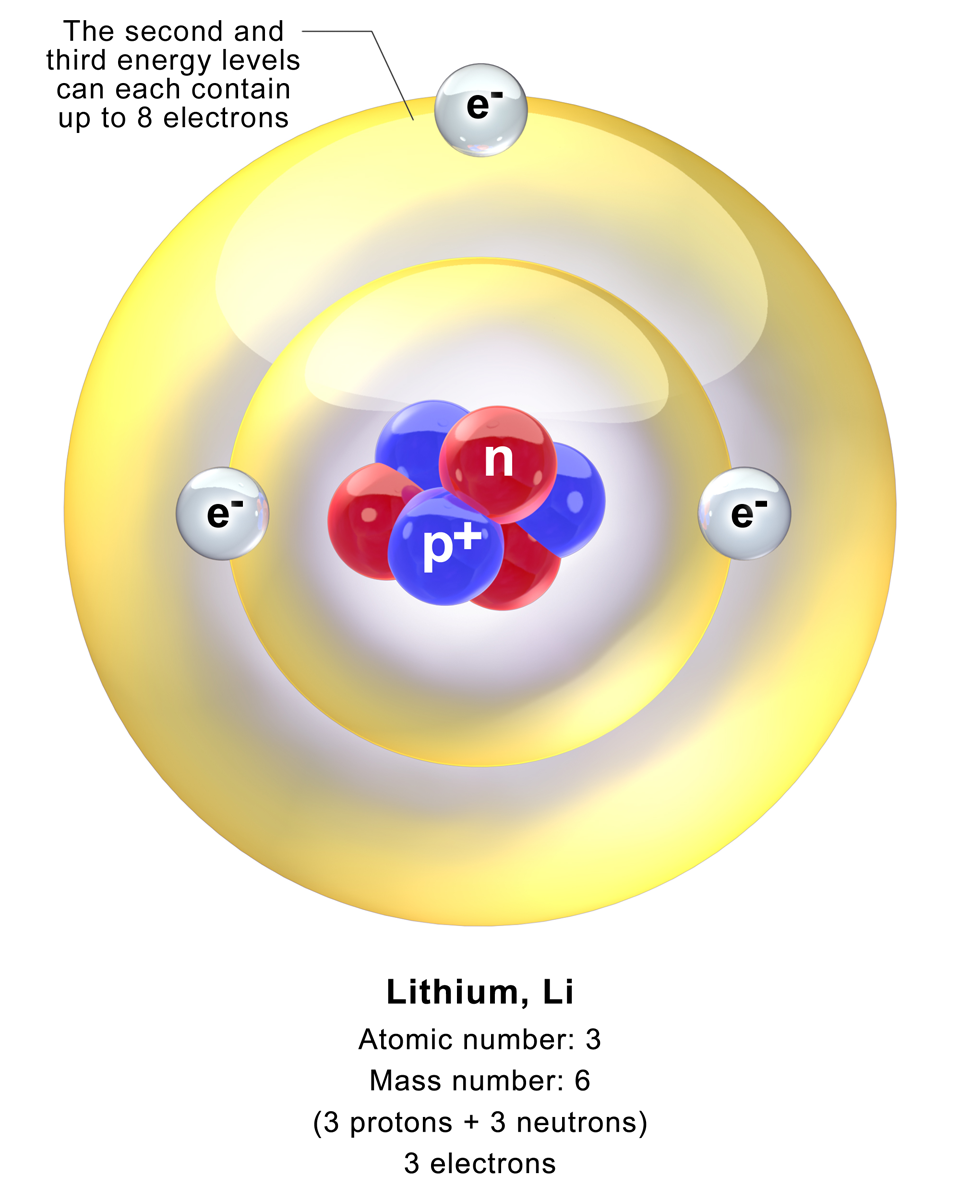

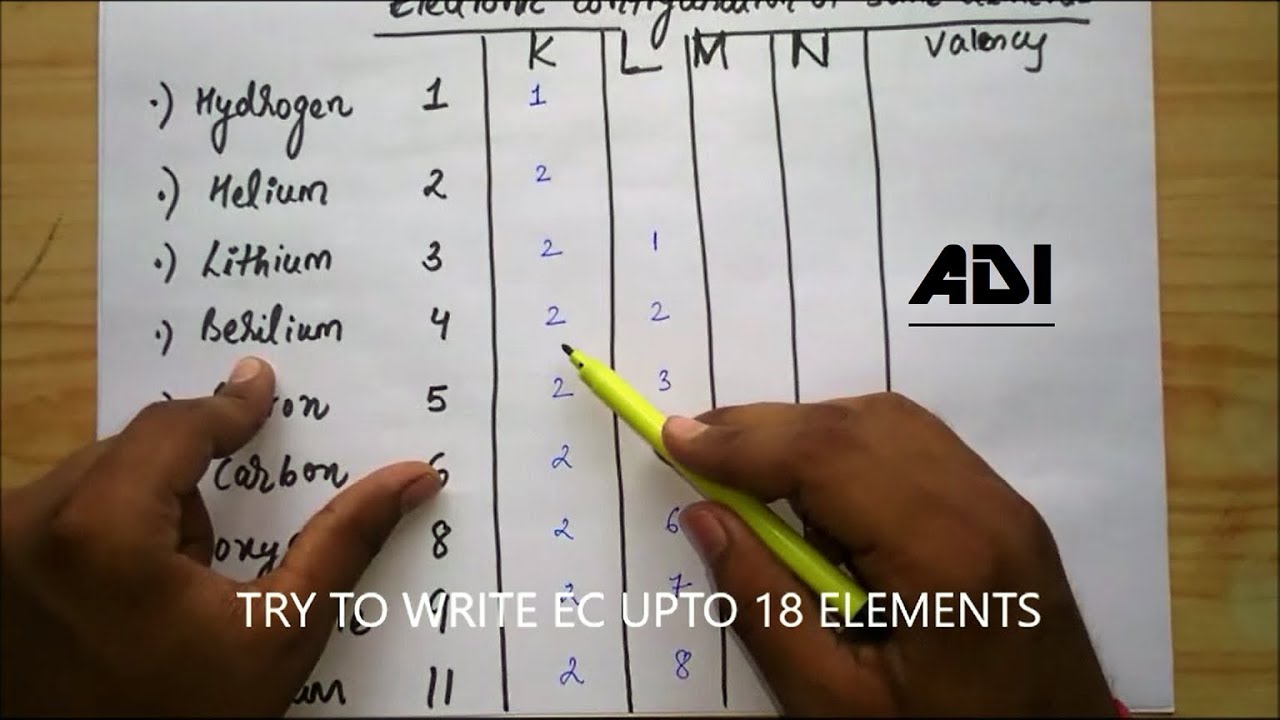

Atomic Number: 3

Atomic Weight: 6.941

Melting Point: 453.65 K (180.50°C or 356.90°F)

Boiling Point: 1615 K (1342°C or 2448°F)

Density: 0.534 grams per cubic centimeter

Phase at Room Temperature: Solid

Element Classification: Metal

Period Number: 2

Group Number: 1

Group Name: Alkali Metal

What's in a name? From the Greek word for stone, lithos.

Say what? Lithium is pronounced as LITH-ee-em.

History and Uses:

Lithium was discovered in the mineral petalite (LiAl(Si2O5)2) by Johann August Arfvedson in 1817. It was first isolated by William Thomas Brande and Sir Humphrey Davy through the electrolysis of lithium oxide (Li2O). Today, larger amounts of the metal are obtained through the electrolysis of lithium chloride (LiCl). Lithium is not found free in nature and makes up only 0.0007% of the earth's crust.

Many uses have been found for lithium and its compounds. Lithium has the highest specific heat of any solid element and is used in heat transfer applications. It is used to make special glasses and ceramics, including the Mount Palomar telescope's 200 inch mirror. Lithium is the lightest known metal and can be alloyed with aluminium, copper, manganese, and cadmium to make strong, lightweight metals for aircraft. Lithium hydroxide (LiOH) is used to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere of spacecraft. Lithium stearate (LiC18H35O2) is used as a general purpose and high temperature lubricant. Lithium carbonate (Li2CO3) is used as a drug to treat manic depression disorder.

Lithium reacts with water, but not as violently as sodium.

Estimated Crustal Abundance: 2.0×101 milligrams per kilogram

Estimated Oceanic Abundance: 1.8×10-1 milligrams per liter

Number of Stable Isotopes: 2 (View all isotope data)

Ionization Energy: 5.392 eV

Oxidation States: +1

Electron Shell Configuration: | 1s2 |

2s1 |

For questions about this page, please contact Steve Gagnon. Mr chainsaw lyrics.

Effective atomic number has two different meanings: one that is the effective nuclear charge of an atom, and one that calculates the average atomic number for a compound or mixture of materials. Both are abbreviated Zeff.

For an atom[edit]

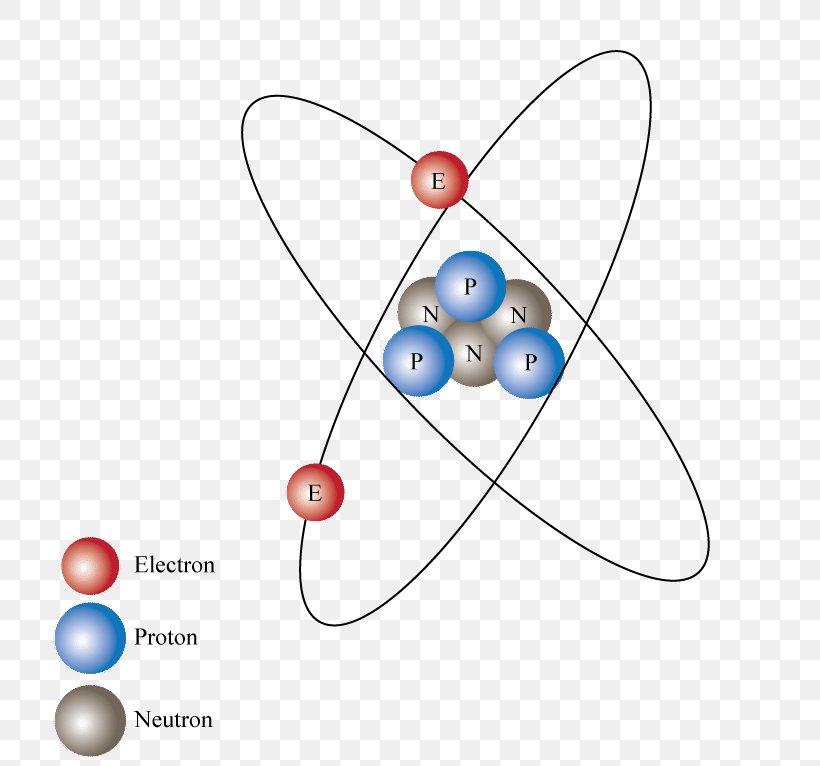

The effective atomic number Zeff, (sometimes referred to as the effective nuclear charge) of an atom is the number of protons that an electron in the element effectively 'sees' due to screening by inner-shell electrons. It is a measure of the electrostatic interaction between the negatively charged electrons and positively charged protons in the atom. One can view the electrons in an atom as being 'stacked' by energy outside the nucleus; the lowest energy electrons (such as the 1s and 2s electrons) occupy the space closest to the nucleus, and electrons of higher energy are located further from the nucleus.

The binding energy of an electron, or the energy needed to remove the electron from the atom, is a function of the electrostatic interaction between the negatively charged electrons and the positively charged nucleus. In iron, atomic number 26, for instance, the nucleus contains 26 protons. The electrons that are closest to the nucleus will 'see' nearly all of them. However, electrons further away are screened from the nucleus by other electrons in between, and feel less electrostatic interaction as a result. The 1s electron of iron (the closest one to the nucleus) sees an effective atomic number (number of protons) of 25. The reason why it is not 26 is because some of the electrons in the atom end up repelling the others, giving a net lower electrostatic interaction with the nucleus. One way of envisioning this effect is to imagine the 1s electron sitting on one side of the 26 protons in the nucleus, with another electron sitting on the other side; each electron will feel less than the attractive force of 26 protons because the other electron contributes a repelling force. The 4s electrons in iron, which are furthest from the nucleus, feel an effective atomic number of only 5.43 because of the 25 electrons in between it and the nucleus screening the charge.

Lithium Atomic Number And Mass

Effective atomic numbers are useful not only in understanding why electrons further from the nucleus are so much more weakly bound than those closer to the nucleus, but also because they can tell us when to use simplified methods of calculating other properties and interactions. For instance, lithium, atomic number 3, has two electrons in the 1s shell and one in the 2s shell. Because the two 1s electrons screen the protons to give an effective atomic number for the 2s electron close to 1, we can treat this 2s valence electron with a hydrogenic model.

Mathematically, the effective atomic number Zeff can be calculated using methods known as 'self-consistent field' calculations, but in simplified situations is just taken as the atomic number minus the number of electrons between the nucleus and the electron being considered.

For a compound or mixture[edit]

An alternative definition of the effective atomic number is one quite different from that described above. The atomic number of a material exhibits a strong and fundamental relationship with the nature of radiation interactions within that medium. There are numerous mathematical descriptions of different interaction processes that are dependent on the atomic number, Z. When dealing with composite media (i.e. a bulk material composed of more than one element), one therefore encounters the difficulty of defining Z. An effective atomic number in this context is equivalent to the atomic number but is used for compounds (e.g. water) and mixtures of different materials (such as tissue and bone). This is of most interest in terms of radiation interaction with composite materials. For bulk interaction properties, it can be useful to define an effective atomic number for a composite medium and, depending on the context, this may be done in different ways. Such methods include (i) a simple mass-weighted average, (ii) a power-law type method with some (very approximate) relationship to radiation interaction properties or (iii) methods involving calculation based on interaction cross sections. The latter is the most accurate approach (Taylor 2012), and the other more simplified approaches are often inaccurate even when used in a relative fashion for comparing materials.

In many textbooks and scientific publications, the following - simplistic and often dubious - sort of method is employed. One such proposed formula for the effective atomic number, Zeff, is as follows (Murty 1965):

- where

- is the fraction of the total number of electrons associated with each element, and

- is the atomic number of each element.

- where

An example is that of water (H2O), made up of two hydrogen atoms (Z=1) and one oxygen atom (Z=8), the total number of electrons is 1+1+8 = 10, so the fraction of electrons for the two hydrogens is (2/10) and for the one oxygen is (8/10). So the Zeff for water is:

The effective atomic number is important for predicting how photons interact with a substance, as certain types of photon interactions depend on the atomic number. The exact formula, as well as the exponent 2.94, can depend on the energy range being used. As such, readers are reminded that this approach is of very limited applicability and may be quite misleading.

This 'power law' method, while commonly employed, is of questionable appropriateness in contemporary scientific applications within the context of radiation interactions in heterogeneous media. This approach dates back to the late 1930s when photon sources were restricted to low-energy x-ray units (Mayneord 1937). The exponent of 2.94 relates to an empirical formula for the photoelectric process which incorporates a ‘constant’ of 2.64 x 10−26, which is in fact not a constant but rather a function of the photon energy. A linear relationship between Z2.94 has been shown for a limited number of compounds for low-energy x-rays, but within the same publication it is shown that many compounds do not lie on the same trendline (Spiers et al. 1946). As such, for polyenergetic photon sources (in particular, for applications such as radiotherapy), the effective atomic number varies significantly with energy (Taylor et al. 2008). As shown by Taylor et al. (2008), it is possible to obtain a much more accurate single-valued Zeff by weighting against the spectrum of the source. The effective atomic number for electron interactions may be calculated with a similar approach; see for instance Taylor et al. 2009 and Taylor 2011. The cross-section based approach for determining Zeff is obviously much more complicated than the simple power-law approach described above, and this is why freely-available software has been developed for such calculations (Taylor et al. 2012).

References[edit]

- Eisberg and Resnick, Quantum Physics of Atoms, Molecules, Solids, Nuclei, and Particles.

- Murty, R. C. (1965). 'Effective Atomic Numbers of Heterogeneous Materials'. Nature. 207 (4995): 398–399. Bibcode:1965Natur.207.398M. doi:10.1038/207398a0.

- Mayneord, W. (1937). 'The significance of the Röntgen'. Unio Internationalis Contra Cancrum. 2: 271–282.

- Spiers, W. (1946). 'Effective atomic number and energy absorption in tissues'. British Journal of Radiology. 19 (52–63): 52–63. doi:10.1259/0007-1285-19-218-52. PMID21015391.

- Taylor, M. L.; Franich, R. D.; Trapp, J. V.; Johnston, P. N. (2008). 'The effective atomic number of dosimetric gels'. Australasian Physics & Engineering Sciences in Medicine. 31 (2): 131–138. doi:10.1007/BF03178587. PMID18697704.

- Taylor, M. L.; Franich, R. D.; Trapp, J. V.; Johnston, P. N. (2009). 'Electron Interaction with Gel Dosimeters: Effective Atomic Numbers for Collisional, Radiative and Total Interaction Processes'(PDF). Radiation Research. 171 (1): 123–126. Bibcode:2009RadR.171.123T. doi:10.1667/RR1438.1. PMID19138053.

- Taylor, M. L. (2011). 'Robust determination of effective atomic numbers for electron interactions with TLD-100 and TLD-100H thermoluminescent dosimeters'. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms. 269 (8): 770–773. Bibcode:2011NIMPB.269.770T. doi:10.1016/j.nimb.2011.02.010.

- Taylor, M. L.; Smith, R. L.; Dossing, F.; Franich, R. D. (2012). 'Robust calculation of effective atomic numbers: The Auto-Zeffsoftware'. Medical Physics. 39 (4): 1769–1778. Bibcode:2012MedPh.39.1769T. doi:10.1118/1.3689810. PMID22482600.

Lithium Atomic Number And Mass